Barcelona’s mayor has defended a ban on flats for tourists, saying “decisive” measures are needed to cut housing costs. Jaume Collboni is determined to implement the plan, which he said would return 10,000 properties to the city’s residents, Spanish media reported.

The decision hit headlines around the world, prompting surprise and threats of lawsuits worth billions of euros but months after Barcelona officials announced plans to rid the city of tourist flats by the end of 2028, the city’s mayor called it a “radical” but much-needed step to curb rising housing costs.

Jaume Collboni said in one of his first interviews with international media since the June announcement:

“It’s a very radical step, but it’s necessary because the situation is very, very difficult. In Barcelona, as in other major European cities, the number one problem is housing.”

Over the past 10 years, rental prices in the city have risen by 68 per cent, while the cost of buying a home has risen by 38 per cent. As some residents complained about the high cost of living in the city, Colboni began looking into the 10,101 licences issued by the city allowing them to rent out accommodation to tourists through platforms such as Airbnb.

The Socialist Party mayor saw this as a relatively quick way to increase the number of residences in the city, while also reducing the number of some of the 32 million tourists who visit the city (1.7 million a year). The mayor added:

“Within the mass tourism model that has colonised the city centre, we have seen significant damage to two things: the right of access to housing, as housing is used for economic activities, and coexistence between neighbours, especially in areas with more tourist flats.”

Catalan city authorities have long tried to address the issue by setting limits on the number of tourist flats. Collboni claimed:

“After many years, we have come to the conclusion that doing something half-heartedly is useless. It’s very difficult to manage and make sure there are no illegal rentals. It’s much easier and clearer to say there will be no more tourist flats in Barcelona.”

While some criticised the years it would take for the measure to come into effect, Collboni set a timeframe of up to 2028 in line with regional legislation that last year limited the issuing of tourist accommodation licences to five years in restricted areas. It was in this clause that Barcelona officials saw their chance: in 2028, when Barcelona’s current number of licences expire, they plan to simply not renew any of them.

The idea has significant limitations, however. Collboni’s term as mayor of the Catalan capital ends in 2027, which could result in the plan being cancelled if elections result in a change of municipal government. Regional law also allows owners to request a one-off extension of up to five years if they can prove they have invested heavily in the property, although Collboni says such cases make up a “minority” of licences in Barcelona.

Instead, he hopes the plan will see more than 10,000 properties returned to the residential property market, where recent rent restrictions and an expected national register aimed at limiting short-term rentals will ideally prevent them from becoming luxury flats or monthly rentals. The city’s team of about 30 inspectors, which officials say identifies more than 300 illegal tourist flats a month, will be beefed up by 10 more positions in the coming months and will continue to operate at full capacity after 2028 to crack down on any illegal rentals that may arise.

The June announcement took many residents by surprise. Jaume Artigues of the Eixample Dreta Neighbourhood Association, which represents an area that contains about 17% of the city’s legal tourist flats – some 1,655 of which are located in the central district, known for its modernist architecture, said:

“We didn’t think it was so radical. I think it’s a very, very bold measure because it will be a tough legal fight against the economic interests of this sector.”

But Artigues is concerned about the protracted timeline, calling it a risky deal in a city where access to housing has already become an emergency. That view was echoed by Albert Freixa of the Eixample Housing Syndicate. He said:

“You can’t promise something for 2028, when there will be elections and you don’t even know if you will be mayor.”

In September, Apartur, an organisation representing management companies and owners of 85% of legal tourist flats in Barcelona province, announced plans to sue for compensation for lost revenue and investment. Describing the city’s plan as a “covert forced expropriation,” the organisation suggested that the claims could be as high as €3 billion.

The country’s constitutional court is also due to review the plan. In February, it agreed to consider a lawsuit filed by the conservative People’s Party, which argued that regional legislation had, among other things, overstepped its bounds when it came to how private property could be used.

Collboni compared the argument to someone trying to open a four-table restaurant in their home. He said:

“No one would do that. Because you have to meet hygiene standards, you have to pay taxes, you have to have full-time staff to operate there. We say no, you can’t do whatever you want with your property. The flat is meant for living, it’s not a business.”

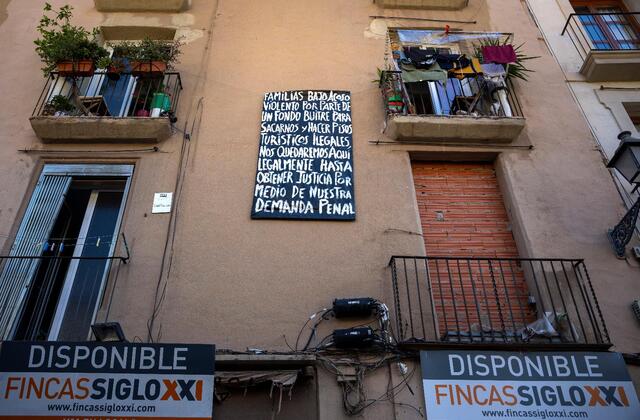

The scandal comes as tensions around tourism in Barcelona continue to heat up. This summer, some people’s anger spilled out after several protesters with water pistols in hand sprayed water on tourists, while others held placards reading “Tourists, go home” and “You are not welcome here.”

According to Collboni, what happened was not a reflection of how most residents feel. He said, pointing to La Rambla, a tourist-infested boulevard with many souvenir shops, as an example of an area that some residents feel has been overtaken by mass tourism:

“But it is true that there is anxiety in the city because we are losing some areas of the city. Tourism has to be limited to what the city can really absorb. We can’t grow indefinitely at the expense of those who live in the city.”