French authorities want to grant legal rights to the Seine River to better protect the world-famous waterway in court and safeguard its fragile ecosystem, as a part of a global movement to grant legal status to nature.

In a resolution adopted on Wednesday, the Paris City Council called on parliament to pass a law granting the Seine legal status so that “an independent guardianship body can defend its rights in court.”

“The Seine must be able to defend itself as a subject of law, not as an object, because it will always be under attack,” Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo said.

Environmentalists have backed the idea of granting fundamental rights to vulnerable ecosystems such as rivers and mountains to better protect them.

In 2017, New Zealand became the first country in the world to recognise the Whanganui River, revered by the indigenous population, as a living being by passing a law combining Western legal precedents and Maori beliefs.

In 2022, Spain granted legal personhood to Mar Menor, one of Europe’s largest salt flats, to better protect its endangered ecosystem.

The Paris Council based its decision on the conclusions of a citizens’ convention on the future of the Seine held in March-May. Fifty randomly selected citizens proposed granting the Seine fundamental rights, such as “the right to exist, flow and regenerate.”

The Seine should be considered an ecosystem “to which no one can lay claim,” where the preservation of life must “take precedence over everything else,” the convention concluded. The convention also noted “positive” changes: there are now around 40 species of fish in the Seine, compared to just four in 1970.

Seine river pollution issue

Swimming has been banned in the Seine since 1923, mainly due to health risks from unclean water and bacteria from human waste.

Cleaning up the murky Seine to make it suitable for athletes to swim in during the Paris Olympics this summer was one of the longest, most expensive and most important projects of the Games.

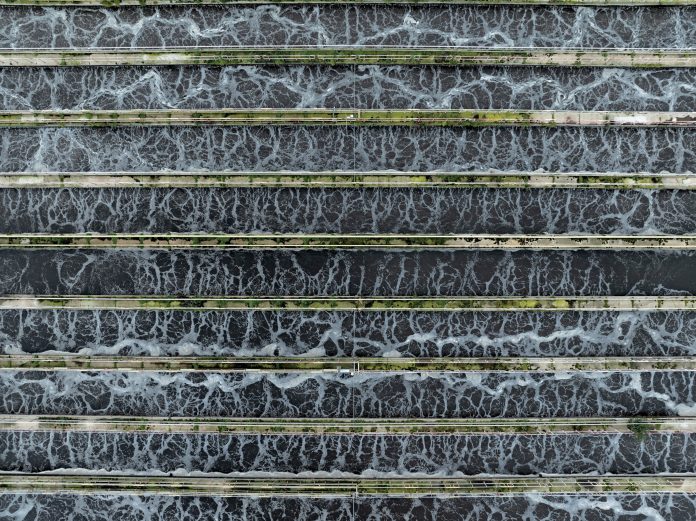

A €1.4 billion state-backed plan involved several years of work on wastewater management, treatment plants, filtration stations and storm basins to reduce bacterial contamination of the river from sewage.

The Seine in Paris is a relatively small and narrow river for a capital city, and it has always been under pressure from the sanitary conditions of the large communities living along its banks. When housing was hastily built on the outskirts of Paris during the post-World War II housing crisis, many of the homes were not properly connected to sewerage networks.

The problem in the following decades was mainly human waste. When heavy rain fell in the Paris area, rainwater entering the sewer system caused overflows, with untreated sewage being discharged directly into the Seine and increasing the presence of faecal bacteria. In recent years, there has been a slow improvement.

Authorities have now counted more than 30 species of fish in the Seine in Paris, compared to three species in 1970.

Among those welcoming the changes are people living in around 250 houseboats in Paris, some of which did not have proper connections to the water supply system, meaning their waste went into the Seine. Following a programme of state-subsidised improvements, almost all of them are now properly connected to the city’s sewage system.